Seneca's "The Madness of Hercules": a stunning performance, a brilliant new translation!

Seneca's "The Madness of Hercules" made its debut this month – and San Francisco actress and singer Grace Wade smoldered as the betrayed Juno in Dana Gioia's stunning new translation of the tragedy.

Actress and singer Grace Wade as the goddess Juno.

This month Seneca made his first appearance in the Bay Area in many years, if ever. The occasion was a staged reading of The Madness of Hercules, on Saturday, June 14, at St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo Park. The dramatic setting in front of the brick portico at dusk intensified a drama that needed no intensification. Let’s hope it’s the start of a Seneca revival. It’s long overdue.

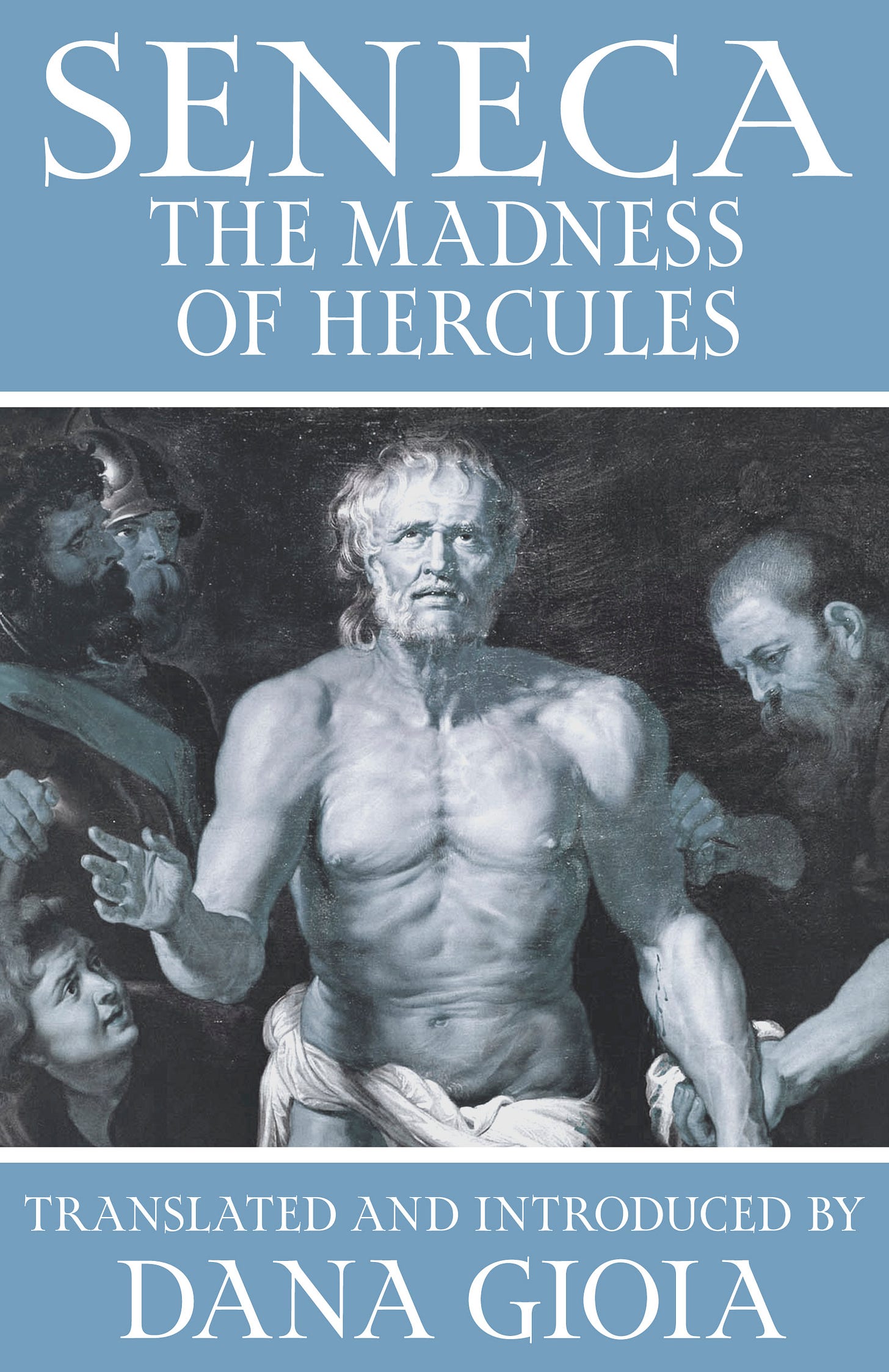

The text is newly translated by poet and former NEA chair Dana Gioia, also a former California poet laureate. The new edition of Seneca’s play was published by Wiseblood Books. (Excerpt from the text coming in another post.) Buy the book. More than a third of the volume is an insightful introduction to “Seneca’s Tragic Vision,” Seneca and European Culture, Roman Tragedy and Roman Politics, Seneca’s life, and more.

The slim volume was praised by poet Frederick Turner: “Dana Gioia's Hercules Furens is a poetic and critical tour de force. By giving us a translation as graceful, vivid, and natural as the original must have been, he paradoxically brings out its essential strangeness to our sensibility. His poetry makes it a sort of dark existentialist Bunraku theater, an allegory of the horrors of Nero's Rome and perhaps a warning to us today. His coinage of the term ‘lyric tragedy,’ connecting the play with the birth of opera fifteen hundred years later, aptly notes that strangeness.”

“It's a fantastic translation, clear and powerful. Dana Gioia does a great job of reconciling Seneca's calm philosophy and emotionally charged drama.” That’s a mini-review by someone known online only as “TheophileEscargot.”

The Antigone Journal ran Dana’s interview with Mateusz Stróżyński, a classics professor at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. Here’s an excerpt:

What drew you to Hercules Furens? Does this tragedy help illuminate or reflect any contemporary situation or circumstance?

DANA GIOIA: I’ve always been interested by verse tragedy, even before I knew I was going to be a poet. I didn’t study Greek tragedy in high school, but I read Sophocles and Euripides on my own (in the Robert Fitzgerald and Richmond Lattimore translations). The first elective course I took at Stanford was a two-term freshman seminar on tragedy taught by a courtly older man who chaired the Spanish Department. (He preferred Racine to Shakespeare and often lamented the haphazard methods of Golden Age Spanish theater.) We read every major tragedian in the Western tradition, except Seneca. That struck me as odd. There was a similar silence at Harvard grad school. Finally, when I left academia, I explored Seneca. I knew Classical Latin poetry but nothing about Roman tragic theater. I read Thyestes in translation, and I was dazzled by its violent splendor. I read the other plays, one by one.

I chose Hercules Furens to translate because of its fabulous account of the Underworld. The play was the missing link between Virgil’s Aeneid and Dante’s Inferno. My interest wasn’t scholarly. Those poems were foundational to my own sense of being a poet. I particularly admired Virgil and Dante’s ability to create powerful, multi-leveled narratives that never lost their lyrical impulse. Musicality is the necessary magic of narrative poetry. It is also a quality missing from most contemporary poetry. From Seneca I learned how to present drama that alternates between regular action and sudden but sustained moments of extreme emotion. You can call these high points verbal arias or poetic oratory. In theater, they are called “show-stoppers”. Seneca’s lyric tragedies helped me write poetic texts for opera.

MATEUSZ STRÓŻYŃSKI: I became interested in Hercules Furens during my research on Euripides’ Heracles and Medea, which I began around 2010. I tried to look at the meaning of infanticide in those two plays, from a psychoanalytic perspective, trying to bring together my interest in Classical drama and psychoanalysis as well as my experience as a practising psychoanalytic psychotherapist. What struck me was that Seneca’s Hercules was much more similar to Euripides’ Medea than to his Heracles. Both seem to give an incredible insight into what has been conceptualized in psychoanalysis as pathological narcissism, especially by authors such as Herbert Rosenfeld, Heinz Kohut, and Otto Kernberg.

Seneca’s Hercules (like Medea) describes a destruction of the inner capacity to love and depend on others, through a desire to control both the self and the others. I think the horrifying sterility of the Underworld in Seneca reflects the inner emptiness and deadness of a narcissistic personality, which inevitably manifests itself in aggression and destruction. But as we can see in Seneca, this narcissistic dynamic is often masked by a narrative of saving the world from monsters in order to bring peace and harmony.

Hercules, at first, is presented by others and himself as a saviour and monster-killer who is going to establish a mythical Golden Age. But the ultimate result is that his wife and his children are destroyed in a most horrifying way.

I think this narcissistic dynamic, which has taken control over Western society in the last few decades, has been depicted powerfully also by J.R.R. Tolkien (the Ring in Lord of the Rings destroys the soul of its bearer in exchange for invisibility and power) and J.K. Rowling (in the Harry Potter novels, the Horcruxes of Voldemort give him ‘immortality’ at the price of splitting his soul). Seneca’s play is unfortunately prophetic in the way it describes how we, as a society, sacrifice what is most fragile and precious in our pursuit of utopian control over our own bodies and minds, and those of people around us.

Read the whole thing here.

I have a special reason for taking an interest in the play, besides my more than a quarter-century friendship with Dana. He dedicated to me, with the words, “Tanquam Explorator.” I treasure that. Thank you, Dana!

Dana Gioia's Seneca: The Madness of Hercules strikes me as nothing short of brilliant. The introduction in itself is something of a masterpiece: I found myself underlining almost every other sentence. He writes an exceptionally lucid and companionable prose, full of insights. I particularly liked his view of Seneca's plays as "lyrical tragedy," in which "the dramatic excitement...is located in the language." The translation of the play itself is clear and eminently readable. Gioia has rediscovered Seneca for us (or at least for me), as a figure at the center of western culture. I had a little bit of the giddy feeling the Humanists must have experienced in rediscovering the classics. Perhaps we need something similar today in response to Artificial Intelligence: a renewed focus on what might be called "Lyrical Intelligence."

This is great to see. I've had a copy of The Madness of Hercules ever since Dana sent it to me when it was first published. I was looking forward to the staged reading, and it was hard for me to miss it when I couldn't make it to the Artists and Art Lovers Retreat at the last minute. At least through what you wrote I have a glimpse of what I missed. And I appreciate the insights from the reviews you posted, including the one from TheophilusEsgargot (LovedbyGodSnail?). Looking forward to the next post with quotes.